Recently I’ve been thinking about all the parts of librarianship that often go unnoticed by the staff within my school. There’s a pressure, I think, to engage in the student-facing, ‘flashy’ side of school librarianship. Library displays draw eyes; bookmark competitions engage students creatively; library lessons are obvious student engagement; the zine collection is an archive of student work.

Even properly labelling and covering the physical library items is something I can point to and say, “this keeps the item from being damaged, and the label tells you where to put it”.

However, when it comes to the cataloguing side of librarianship, the work largely flies under the radar – despite being integral to ensuring the library runs smoothly.

Since I arrived at Chetham’s just over five years ago, one of my biggest projects (read: bugbears) has been mitigating the user-unfriendliness of the school catalogue.

The school library uses Reading Cloud software: a cataloguing software designed for schools and easily accessible for non-librarians to catalogue with. (Not a MARC record in sight!) It is functional for most school library collections, but it is not (and does not claim to be) designed for music libraries in the slightest.

Our school library has just over 36,000 items, which is quite small for an academic library, but rather large for a school one. Since Chetham’s is a specialist music school and the library is a combined school and music library, over 20,500 of these records are sheet music (including almost 10,000 chamber music sets). I’m putting this into perspective to demonstrate that it is feasible to work with all of the items in our collection (no awful surprises), but impossible to hold the collection in one head.

The catalogue is necessary for telling me what is in the three libraries (and where it is located), however, the Reading Cloud Software is not ideal for sheet music retrieval.

While library staff have access to a more advanced management system, the main difficulty is that Reading Cloud’s student interface has a slow and buggy Advanced Search. This is not such a problem for a regular school library, where most books have a single title, but music is far more complicated. It is frequently necessary to be able to specify the title and the composer of a piece before anything can be located.

Reading Cloud also allows users to easily sort their search by author, but not composer. It is possible to use the sidebar facets to remove CDs from a search (thank goodness). But music searchers must still attempt to navigate a janky Advanced Search that does not effectively filter by field, meaning that it is unrealistic to expect children or even staff to necessarily find what they are looking for – particularly with popular composers like Mozart or Beethoven, or any composers who don’t use opus numbers.

The Quick Search does not, automatically, search across multiple fields – and strict cataloguing standards assume users can use an Advanced Search if necessary. Reading Cloud, however, seems to expect students to get by with only the Quick Search function, the high-functioning Advanced Search being exclusively accessible to the library staff accounts (i.e. accounts with catalogue-editing permissions).

Which means, really, if I want the students to be able to use the library catalogue to suit their musical needs (and I do: the Year 7 literacy class receives a whole lesson on the library catalogue each year), the school catalogue must be adjusted to work as much like a Google search as possible. This means adapting my cataloguing to allow a Quick Search to retrieve the items requested.

Librarianship teaches that a good search system has two goals that it must strive for: Retrieval and Precision.

Assuming the library has the required item in stock, Retrieval describes whether the search returns the required item at all, and Precision describes how many unrelated items it also displays alongside the required item.

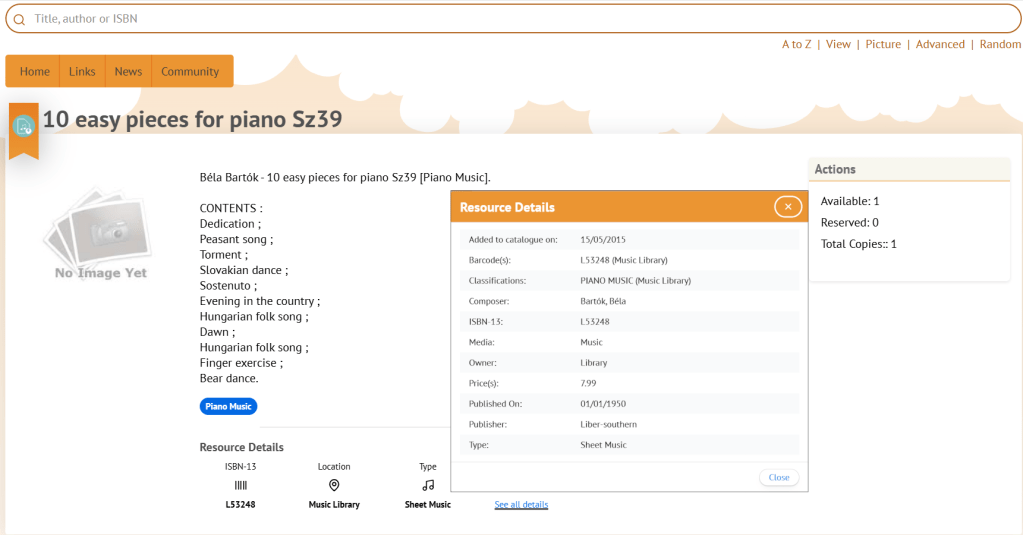

Enter my system. Since I started working at the school, I have been adding a line, purely for retrieval purposes, to the top of the summary field in each record:

Firstname Surname – Title [Classification or Location].

Although this line does not follow any orthodox cataloguing practice, these combined descriptors all have identical punctuation formats and allow the searcher to effectively apply a filter (or expander) to their queries without resorting to the Advanced Search (which, even for library staff, is slower than the Quick Search). This speeds up the time devoted to finding items, and makes it easier for students, school staff, and the library assistants (and me!) to check for items on the catalogue.

Children (at least the children in my school) have the tendency to assume that if something goes wrong they are at fault or have messed up. And it is both undermining to their confidence to be confronted with a rickety system, and embarrassing for me to have to explain that something should have been brought back but just wasn’t – often not through any fault of their own.

Bartók Case Study: This is what I’m Bar-Talking About

As an example of further back-end work that will never be noticed, last week I spent a sizeable amount of time working on the Bartók sheet music. It started because I wanted to add catalogue numbers to the records to make it clear in the catalogue exactly which Bartók sonata (for example) a particular record, described only as ‘sonata for piano’ was referring to. (If composers would just opus all of their compositions, my work as a music librarian would be much easier!)

First, I did a little research into Sz vs BB numbers, deciding which catalogue number system I wanted to use. I chose Sz because it seemed to be the more common system to be used these days, including by the Petrucci Music Library (IMSLP) of online scores, frequently used by the students and staff to supplement the school’s physical sheet music library. Even if that choice proves over time to be the wrong one, the Sz numbers are still useful for identifying items now and will help future cataloguers change the system over later if necessary without needing to consult the physical music.

After settling on using Sz, I then printed off a list of all 133 records of Bartók sheet music that we currently have in the school library. I went through each item in turn and worked out each item’s Sz number.

Some of the music was badly described, so I standardised how they were described in the title field a little more, then each item was given a summary entry:

Béla Bartók – Title [Classification or Location].

If the item required a contents list, this was also added, alongside any additional tags and missing information that was easily accessed from the original record (but I did not allow this to slow down or side-track the main project). Fortunately, most of the time, I was able to exclusively work from the existing record, which saved a lot of time. However, occasionally a record had been poorly catalogued to begin with, and in those instances I did return to the physical item and overhaul the full record.

Since completing this project, every piece of Bartók music we have in the school library is now retrievable searching (in the Quick Search):

- just the Sz number (e.g. Sz80)

- Bartók or Bartok and a title (e.g. Bartok sonata)

- Bartók or Bartok and the location (e.g. Bartok piano music).

Or any combination thereof (e.g. Bartok sonata Sz80 piano music). None of this was possible before this project, and the addition of Sz catalogue numbers for the title fields means the pre-existing Advanced Search option is more useful for library staff as well.

Incidentally, during this process I discovered that Bartók actually only wrote one piano sonata important enough to justify its own Wikipedia page, which is why it was listed in the catalogue as merely “Sonata for piano” to begin with. But having the full record and retrievability still ensures the music will now be retrieved if a kid searches for “piano sonata Sz80” or “Bartok piano sonata”.

I find it harder to advocate for this kind of invisible work because, if a student or staff member is looking for Bartók in the catalogue now, all they will discover is a lack of friction finding it. They will not notice the ease, and it is not as attention-grabbing as a new library display or bookmark competition. But long after the display comes down, and the bookmarks have been replaced, this string of text in the summary field will still be helping Chetham’s students and staff to navigate the catalogue independently without being punished for a catalogue system that wasn’t designed for them.